One of the difficulties in doing molecular research on the kidney is the diversity highly specialized cells that exist in the glomerulus. As a result, it is important to be able to isolate glomerular tissue from the surrounding kidney. A recent paper in KI detailing a method for isolated podocytes reminded me of a relatively simple technique that I was taught a few years ago for glomerular isolation in mice.

The technique was first described in this paper from 2002 but in brief, it involves injecting the mouse heart with deactivated magnetic beads (after euthanizing them of course). Some of these beads (which are just 5µm in diameter) get trapped in the glomerular capillaries. The kidneys are then removed, minced, digested and passed through a 100µm strainer to remove any larger particulate matter. Finally, the remaining tissue is suspended and exposed to a magnet to pull the glomeruli (with the beads inside) out of the mixture. The glomeruli are then left stuck to the wall of the tube next to the magnet and they can be easily removed.

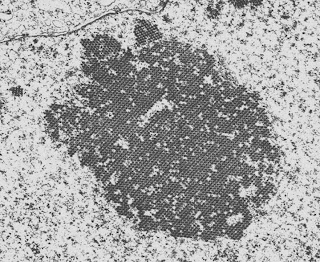

The picture below is a low-power view of the glomeruli following isolation. You can see that there is very little non-glomerular tissue present, which is remarkable given that the glomeruli make up such a small proportion of renal tissue.

Below is a higher power view of 3 more glomeruli following isolation. You can clearly see the microbeads trapped in the glomerular capillaries. Cool science. (Click on any image to enlarge)

The technique was first described in this paper from 2002 but in brief, it involves injecting the mouse heart with deactivated magnetic beads (after euthanizing them of course). Some of these beads (which are just 5µm in diameter) get trapped in the glomerular capillaries. The kidneys are then removed, minced, digested and passed through a 100µm strainer to remove any larger particulate matter. Finally, the remaining tissue is suspended and exposed to a magnet to pull the glomeruli (with the beads inside) out of the mixture. The glomeruli are then left stuck to the wall of the tube next to the magnet and they can be easily removed.

The picture below is a low-power view of the glomeruli following isolation. You can see that there is very little non-glomerular tissue present, which is remarkable given that the glomeruli make up such a small proportion of renal tissue.

Below is a higher power view of 3 more glomeruli following isolation. You can clearly see the microbeads trapped in the glomerular capillaries. Cool science. (Click on any image to enlarge)